A few beers, a pocketful of change and the next thing you know……………

What follows is a letter from Baldwinite Rudy Marco to a co-worker, Jack Robinson about Marco’s post-WWII re-entry into society and education. It was written in 2005.

Rudy left BSHS to enlist in the Navy in WWII. After the war he worked on the Esso Pittsburg, a coastal oil tanker, saving up money and finishing his high school courses so he could attend Tulane University.

Rudy sent the story to his nephew, Jim Marco ’65 and Jim passed it along to B.A. Schoen ’65. B.A. loved the story and his interest was piqued: “What happened to the characters in this story?

“Tracking them down was actually pretty easy”, says B.A. “I sent a few emails out to two colleges in Mississippi and struck gold in the form of Mr. Charles Sullivan, Archivist od Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College in Perkinston, MS.”

Mr. Sullivan did the heavy lifting and his letter which follows the story ties it all up with a bow that includes a couple of All Americans and a Co-National Championship.

Dear Jack,

As I told you on the phone, I enjoyed your long letter about playing football at Yale after the war. It brought back fond memories of those years. If you remember, I told you I had a story to tell you but it was too long to tell on the phone. I promised to write it and send it to you. I didn’t realize how long it was until I began writing it and it grew like a department of the government. This is it. Sorry it took so long.

Yes, those years following the war were happy times, at least for most of us. The bars were filled every evening with ex-servicemen renewing friendships after two, three or four years of separation. Their newfound freedom from those mindless military years was like the celebration of a mass jail break. Seeing old classmates, renewing friendships, walking familiar streets, wearing civilian clothes, eating home cooking and having an entire room to ourselves felt like a return to paradise. The celebration was temporary for some who soon departed to other places and friends met during their years in service. “How you gonna keep ‘em down on the farm after they’ve seen Paree,” or even sunny California? Some found the return to family problems intolerable and they left. Many of us, for the first time in our lives, thought about attending college. Few realized that those years would be the crossroads of their lives. Why would we? We were too young and too caught up in the celebration.

The busiest bar in Baldwin was the Douglas Inn. The “DI” was a large old house nestled in the trees on a quiet street. It had been a speakeasy during prohibition and later became a bar and restaurant with an outdoor picnic area. The owner, John, was a middle-aged German who looked like an aging Max Schmeling. John and his unmarried daughter, Anna, found themselves in the right place at the right time. The war ended and thousands of GIs returned home and needed a place to hang out and the DI met all their requirements. It had a dance floor, cheap beer and Otto, the waiter who supplied the hospitality and good cheer that John lacked. Otto was a short, bald headed German with very heavy accent. He was in his late seventies, but he always managed a smile and a pleasant word as he carried trays of awful, but cheap, Linden beer to the crowded tables. We thought Otto was ancient then. Now that my perspective has changed, I wonder how in the world he managed it all. The entertainment in that pre-television world was a juke box which never stopped playing Vaughn Monroe, Perry Como, Peggy Lee, Sarah Vaughn, Frank Sinatra and Nat Cole singing those lovely ballads. Whenever I hear “To Each His Own,” “The One O’clock Jump,” “Long Ago and Far Away,” the memories, the faces, and the feelings return in a sharp focus as though it all happened yesterday. As you might suspect, the music and the dancing at the DI were frequently interrupted by fights. It must have been some kind of macho tribal instinct. Is a stranger came into the DI, it wasn’t a problem. However, when a group of guys came in from out of town, they were probably looking for trouble, especially if they had had a few too many. Women didn’t come to the DI or any other bar, unescorted. Sounds strange and unbelievable to the youth of today but that’s the way it was. Most of the crowd were single guys who, after all those years in the service, became as aggressive as tom cats in the presence of all the females and all that beer. Whatever the reason, it was not uncommon to hear voices raised above the music then the sounds of chairs and tables sliding and crashing to the floor. When a fight started, john would shout, “Outzide! In zer parking lot! Outzide, bevore I call zer poleeze.” John eventually had enough and sold that bar to an out-of-towner named Sam. Sam had to be impressed by the DI’s nightly cash receipts, but he must have surveyed the business on a night when there were no fights. After his first month, he said he ought to convert the dance floor to a boxing ring, hire a referee and advertise the fights. If he had, one of the main attractions would certainly have been Fred Cruger, known to everyone except his family as “Dutch.”

Dutch wasn’t a regular at the DI and so far as I knew he never had a fight there. It wasn’t that he was a loud mouthed troublemaker who looked for fights. He was, to the contrary, very private and soft spoken. In all the years I knew him, I never saw him in a fight, anywhere. His fights seemed to occur when a few of his friends, feeling secure in his company, tended to become belligerent with others and Dutch was a guy who stood by his friends. Whatever the reason, stories of his fights quickly circulated, somewhat exaggerated I am sure, and his reputation grew. It was a reputation that brought problems. Like the gun fighters of the old West, it made him a target for anyone who sought to challenge it and, I am sure, it was one of the reasons he didn’t become a regular at the DI. Dutch was built like the next larger size Rocky Marciano, a little taller and a few pounds heavier. I can recall walking along 42nd street towards Fifth Ave. years later and seeing a man walking towards me who I thought was Dutch. He seemed a little too small and as he got closer, I realized it was Marciano himself. Dutch had been a big, strong, athletic youngster who managed to make the varsity football team when he was only a freshman. He had attended the local parochial school and I am quite sure it took him more than eight years to get through the eighth grade. Don’t misunderstand me, Dutch wasn’t stupid, far from it. He just wasn’t interested in school as an educational experience. A high school for Dutch was a team to play for and a classroom was a place to wait until football practice started. His years in the parochial school had several lasting effects on him. He was a devout Catholic all his life. He once told me he got on his knees every night to pray. He also had a burning desire to play football for Notre Dame. Dutch left and three and a half years later was discharged into an uncertain future with very limited prospects. If he ever had any serious thoughts of going to college, his terrible academic credentials and his age after almost four years in the Navy had ended them forever. Dutch’s father worked for Mobil Oil in Manhattan and managed to get him a job as a deckhand on a small Mobil river tanker which delivered oil products along the Hudson and the Jersey Shore. I am sure his father felt it was a good way to keep him out of bars, away from his friends and out of trouble. Dutch thought it was an easy job and suggested to me that working on a ship was a great way to save money.

I had other plans. I wanted to take advantage of the GI bill and attend college but I had quit high school midway through my junior year to join the Navy. College would require that I finish high school and for about a year and a half I took courses anywhere I could to meet college entrance requirements. By the spring of 1947, I had finished and, largely on Dutch’s advice, took a job on an oil tanker to save some money for college. It was aboard the Esso Pittsburgh that I met a high school football player from Alabama named Walter Sherer. In Walter’s world, cotton wasn’t king in the south, it was football. We were on the same watch and talked football, endlessly. By the time we parted, Walter had convinced me that the best college football I the country was played in the Southeastern Conference and it was the duty of every red blooded Alabama boy to try to play football for the Crimson Tide. If you were an outstanding football player in the South, Walter said, there were no limits to your possibilities. After working on the tanker for three months, I returned to Baldwin to prepare for the trip to New Orleans and Tulane and Walter headed back to Alabama to pursue his dream of playing college football. When we parted, we were both certain we would never meet again.

Baldwin hadn’t changed much. The bars were still busy but the party had been slowed by the departure of many to full time employment or college. Dutch happened to be home when I returned and he had learned that the Long Island Indians, a semi-pro football team, was holding tryouts that Friday evening. He wanted to give it a try so four of us drove to Valley Stream that evening to watch his tryout. We were all surprised by the size of the crowd. The field was filled sideline to sideline with guys of all shapes, sizes and ages wanting to tryout. There were hundreds of them, mostly ex-servicemen who must have had an undying love for the game because there wasn’t much money in it. Dutch was visibly disappointed by the size of the crowd and didn’t even get out of the car. He felt it would be impossible to get a decent tryout with crowd that large so we headed back to the DI for a few beers.

One beer lead to another and as we drank Dutch’s disappointment seemed to deepen. It was clear that he sensed the football parade had passed and it wasn’t coming back. Many of his friends were going to college and here he was, an aging high school dropout with a very unpromising future. As the evening moved along, my conversations with Walter Sherer aboard the Esso Pittsburgh came to mind. I knew Dutch had been an excellent football player in his abbreviated high school career and it seemed his football talent was being wasted because, if Walter Sherer was correct, Dutch didn’t live in the South. I told them about my conversations with Walter and everyone began to laugh and joke about the thought of Dutch going to college. Even Dutch had to smile at the impossible fantasy. The idea was carried along on a stream of beer and progressed from an amusing conversation to a challenge. Someone suggested that I call Walter and ask what Dutch’s prospects would be in the South. Someone else emptied the change from his pocket and offered to pay for the telephone call. I said I would try if Dutch were willing to go and Dutch’s response was rapid, but skeptical. He said, “Sure. Why not?” The others began to empty the change from their pockets and I wondered how I could get in touch with Walter. I didn’t know his address or telephone number and it was now close to midnight, not the best time to wake strangers to ask them questions. They were excellent reasons to put the whole thing off until the next day but the beer had rendered any reasonable evaluation, unwanted and useless. Everyone wanted an answer and they wanted it now. I remembered Walter’s standard answer when asked where he came from. He always answered with hometown pride, “Jasper, Alabama, the home of Tallulah Bankhead.” Well, that was a starting point. I took a handful of coins to the pay phone and began the search with a call to Information in Jasper, Alabama.

There were several Sherers in the Jasper telephone directory. After calling several wrong numbers, I succeeded in waking Walter’s mother from a sound sleep to learn that Walter was not home. He had gone to Mississippi for football practice at Mississippi Southern University. Another handful of coins were fed into the pay phone and a telephone was ringing in the athletic dorm at Mississippi Southern. I remember the phone rang for quite a while, long enough for me to have a serious second thoughts. Eventually, a sleepy football coach picked up the phone. I told him I was calling from New York and needed to talk to Walter Sherer. He must have concluded it was important because he didn’t even ask why I was calling. He said he didn’t know Walter but the name was familiar and if I would hang on he would locate Walter’s room, wake him and bring him to the phone. Five or ten fifteen minutes later, sleepy Walter came to the phone convinced that either an emergency had happened or he was the victim of a very unfunny practical joke. When he learned who it was, he asked why I was calling. My fear of getting a negative answer to the question I was about to ask caused me to improve the odds with little exaggeration. I said I was standing next to a friend who made the All-Nassau County High School football team before he left school and went into the service. He was six feet two, weighed 225 lb. and could run a hundred yards in a little over 10 seconds. I then asked Walter if he thought Dutch could get on the team there. Walter must have sensed some exaggeration but his southern civility kept him from questioning the description. In his southern drawl he answered, “Hell, if he’s half as good as you say he is, all he has to do is show up.” Then he quickly added, “But he better get down here real quick because practice started two weeks ago and they’re getting ready to make some cuts.” I asked how quick and he said, “Right now, tomorrow.” I said it would be impossible to get there the next day and he answered, “Then as quick as he can. He may be too late now.”

Back at the table the news was greeted with laughter and excitement, but it didn’t last long. Reality rapidly began to smother the euphoria. Dutch had been standing next to me at the telephone, heard all the exaggerations and was well aware of the details which had been omitted. Any one of them could disqualify him and make the long journey to Mississippi another painful disappointment like the tryout earlier that evening. Walter Sherer wasn’t the final judge and had only offered his opinion that Dutch had a chance if he were willing to travel all the way to Mississippi. He had also cautioned that it might be too late already, let alone when Dutch arrived. The risks had no effect on Dutch’s new found enthusiasm. He said he could leave the next day and felt his old, beat up 1935 Ford roadster could make the trip if it weren’t pushed over 30 mph. The 1935 model year was the second year Ford made V8 engines and it was a notorious oil burner that trailed a cloud of blue smoke as it burned a quart of oil every 50 miles. It was a V8 in name only because one cylinder had been missing and silent for months. Someone had said that Dutch was driving the only V7, semi-diesel in the world. In spite of all its problems, Dutch was confident the car would get there if the oil level were constantly checked and kept high. We estimated that Jackson was about 1300 miles from New York. At thirty miles an hour, the trip would take about two days and two nights of continuous driving with no time to stop at a motel. Dutch asked whether anyone wanted to come along to share the driving because he couldn’t do it alone. The only seat in his coupe was the bench seat with a small storage space behind it. It had no rumble seat only a large trunk, large enough for someone to lie in. as it turned out, the limited seating wasn’t a problem because everyone quickly explained why they couldn’t go. As the negative responses were made, I began to feel guilty about having started the whole idea so I reluctantly volunteered to go if no one else could. Sure enough, that’s the way it turned out. The party ended on that sobering note and Dutch said he would pick me up at 10 am the next morning. He then added that we would need to drive to the Strauss Auto Supplies store in Freeport to buy six gallons of lubricating oil before we started the trip.

When I awoke during the night my thoughts turned to the events of the evening and I couldn’t fall asleep again. The phone calls and the commitment to make the trip which seemed sensible the night before now seemed bizarre. As I tossed in bed, one potential problem piled upon another and it became clear that we had entered into a foolish alcohol drenched pact. Two days and two nights of continuous driving in a modern automobile would be an ordeal. The likelihood that Dutch’s broken down, uncomfortable V7 could even survive the trip was remote. If it did, was there really any chance that Dutch could get into a college? If he did get in, how would I get back home? If he didn’t get in, how would we both get home? Surely, the car wasn’t capable of a round trip. Perhaps Dutch would rethink the whole crazy plan and call it off in the morning. I couldn’t. it would have to be up to him. On that hopeful note, I managed to fall into an uneasy sleep.

Dutch showed up about 10 am, unshaken in his determination. After purchasing six gallons of oil, we unfolded a road map and planned the trip. It didn’t take long. We decided it would be wise to avoid the parkways and throughways because the V7’s thirty mile an hour speed limit would be dangerously slow and there would be no alternative transportation available to get home should it break down. Our plan was to pick up Rte 11 somewhere in Pennsylvania and take it all the way to Mississippi. We headed west on the Sunrise Highway with Dutch at the wheel for an uncertain passage through New York City.

Sixty years later, I still have vivid memories of the trip. By the second evening, we were so tired we needed to switch drivers every hour. Neither of us had a watch so we used the map to locate a town about thirty miles farther along to make the next change. We tried to arrange the driver changes so they coincided with the oil checks and refills but the plan never seemed to work out in practice. I slept sitting upright on the passenger side, but Dutch found it too uncomfortable. When it was his turn to rest I would open the trunk so he could stretch out on the truck floor. He was literally locked in the trunk until I stopped again. We were both lucky he wasn’t asphyxiated as he slept. He, for obvious reasons, and I because it might have been very difficult to explain to local police how I came to be driving a car with a New York State license plate and a dead man in the trunk. Some stretches of the road consisted of a series of steep hills which presented special problems for our underpowered V7 and any trucks that were following close behind us. The V7 with its weak engine slowly crawled to the crest and the trucks were required to crawl behind us as they followed. When we reached the crest, we ignored our self-imposed 30 mph speed restriction and gunned the old V7 to get enough momentum to climb the next hill. Truck drivers who were close behind on the upgrade expected us to allow them to pass on the downside. When we gunned down the old Ford on the down side, they couldn’t pass easily and the downside ride became a wild race downhill with the big rigs blowing their air horns as they tried to pass while we listened for any hints of our engine’s demise. Driving all night through miles of unlighted southern farmland seemed like an endless surreal journey. The only lights were receding red taillights of cars that passed us and the bright, blinding headlights of occasional oncoming traffic. There were no lights on the roadside and the Ford’s dim headlight illuminating the white lines of the highway were our only guide through the blackness. The effect was hypnotic, sleep inducing and dangerous. Finally, we arrived at Mississippi Southern, unshaven, unwashed and completely exhausted. We located the athletic dorm and learned that Walter had been cut from the squad and sent to a junior college in Perkinston, Mississippi, about 60 miles south of Jackson. It was a crushing disappointment but we had no alternative other than getting back in the car and heading for Perkinston.

The fall semester had not yet begun and the junior college campus seemed completely deserted under the blazing Mississippi sun. No difficulty finding a place to park, the lot was empty. We parked close to the official looking buildings at the far end of the lot. It was simply too hot to walk any distance. I have never asked Dutch how he felt at that moment but he must have felt as I did. The realization that we were about to get an answer to the question that had driven us all the way to Perkinston seemed to energize ne. One way or the other, it was all about to come to a rapid conclusion. Then a familiar figure came around the corner of one of the buildings with his hair still soaked from a shower just taken following morning practice. It was Walter. I called out to him: he turned in our direction, recognized me and picked up his pace as he walked towards us.

“I wondered what had happened to you guys,” he said.

“Walter, this is Fred Cruger.”

Walter looked at Dutch and it was clear, he was impressed. He extended his hand and said, “Hi, Fred. Glad you got here. Come on, let’s go see the coach. He’s still in the locker room.”

We headed for the locker room and I began to get a nervous feeling in my stomach.

“Ah wondered whether y’all were comin’.” Continued Walter. “Ah didn’t know how to get in touch with you when MSU sent me down here. Ah told ‘em to look out for you and tell you where ah went.”

He lead us toward a one story building next to the football field. The windows were all open and, as we neared it, we could hear voices and the sounds of running showers. We walked into a room full of players getting dressed or heading to the shower. Stretched out on one of the benches, completely naked except for a towel covering his privates was a balding, heavy set, middle aged man with his eyes closed as he rested while waiting to get into the shower room.

“Coach.” called Walter. The middle aged man opened his eye and turned his head in our direction. “Coach, I want you to meet Fred Cruger. He’s the fellow I told you might be coming down here from New York. Fred just got out of the service.”

The coach stood up, rapidly tying the towel around his waist. As he did, he looked at the big, burly, and unshaven prospect that stood before him. He extended his hand and his smile revealed the delight he felt at his unexpected good fortune. “Hi Fred. Pleased to meet ya. What position did you play in high school?”

So far, so good, I thought.

“I played end and sometimes fullback.”

“We can’t afford backs as big as you. You’d play in the line here.”

“OK. Sure.”

“We’re gonna have to get you enrolled. You graduated from high school?”

“No.”

“Oh.” He paused. “You completed two years?” There was a slightly begging tone in his voice.

”No,” answered Dutch.

The moment of truth arrived.

The coach looked down and a look of concern replaced his smile. When he looked up he had to notice that his concern migrated to Dutch’s face.

“Well, don’t worry about that. We can take care of that Fred. Next week we’ll have to get you registered and courses scheduled. I’ll help you with that. I want to be sure you get the right classes and the right instructors. ”

Dutch nodded his agreement, “Sure coach.”

“We have two a day practices here. We just finished the morning practice and we’ll have another this evening. It’s too hot to practice during the day. I’d like to have you practice with us tonight if you feel you can.”

“Sure coach, but I have to take Rudy to New Orleans so he can get a train back to New York. I don’t know how long it will take to get there and get back here.”

Dutch drove me to New Orleans and, incredible as it now seems, returned in time to practice that evening. About one month later, on a weekend when Tulane wasn’t playing a home game, I went to Perkinston to watch them play. Just before the kickoff, the announcer introduced the starting lineup as each starting player ran onto the field, “At right guard, Walter Sherer, from Jasper, Alabama. At right tackle, Fred Cruger, from Hattiesburg, Mississippi.”

The man seated directly in front of me turned to his wife and asked, “Fred Cruger form Hattiesburg?”

He paused and the added, “Why I know his Mommy and Daddy.”

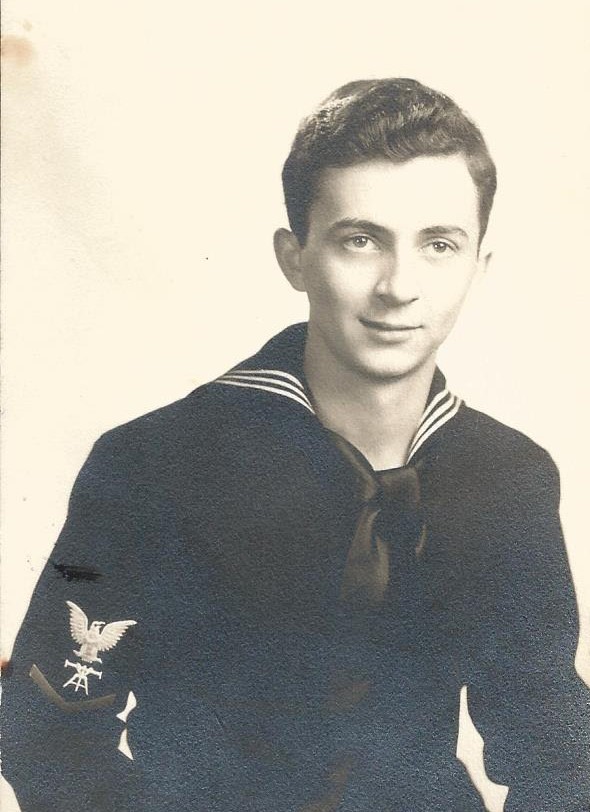

Rudy Marco – Then

Rudy Marco – Now